Japanese international cooperation has supported primary mathematics programmes in Africa for more than two decades

- September 4, 2024

- Education

- 0 Comments

By Takuya Baba, Professor, Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hiroshima University, and Atsushi Matachi, Senior Education Advisor, Japan International Cooperation Agency

Japan’s international cooperation programmes in basic education, reflecting its own historical development experience, have emphasized the use of existing systems and resources to help build institutions. This blog draws from a background paper prepared for the 2024 Spotlight Report on foundational learning in Africa: Learning Counts.

Japan’s approach to international cooperation, as reflected in its ODA Charter introduced in 1992 and last updated in 2023, has been shaped by its own historical modernization experience. Emphasis is placed on helping partner countries’ self-help efforts. Cooperation has been directed at improving capacity using local systems to ensure independence and sustainability. There have been three policy documents in education in the past decade. The latest one published in 2015 is Learning strategy for peace and growth: Quality education through learning together, which added human security as a reason for investing in education in line with Japan’s ODA Charter.

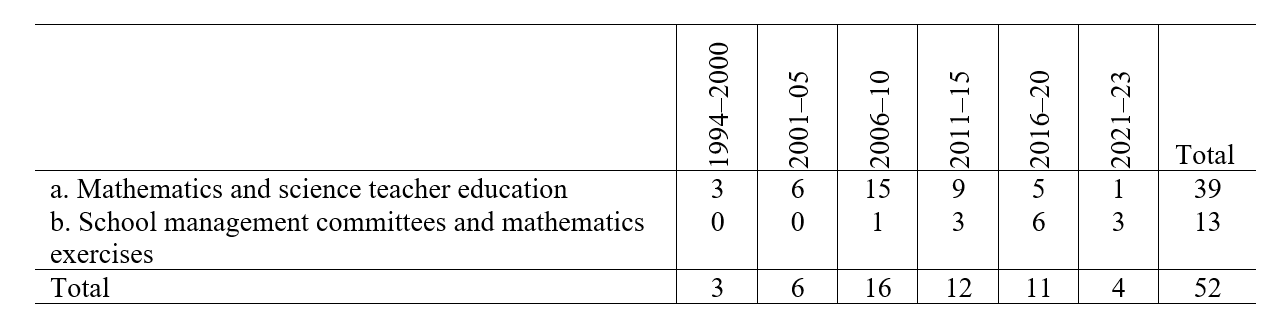

Although initially Japan’s programme did not focus on basic education, this changed gradually in the late 1990s increasing the number of the projects for basic education with a focus on mathematics and science education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has implemented 52 technical cooperation projects on mathematics to this day, which can be grouped under two types.

Japan’s primary and secondary education mathematics projects in Africa, by starting year and type

Some projects have focused on mathematics teacher education

The first type of project focused on teacher education. In Kenya, the Strengthening of Mathematics and Science in Secondary Education (SMASSE) project began in 1998 and was the first basic education cooperation project in sub-Saharan Africa for Japanese cooperation. SMASSE aimed to shift from the traditional lectures and management to a new teaching approach and a management cycle emphasizing reflection and improvement. It used the cascade training approach. The government sustained the in-service training system with its own resources (setting aside 1% of each secondary school’s tuition fees and some funds at the national level).

In Zambia, the project, which began in 2005, used resource centres to support professional development. This approach was followed partly to build on existing institutions of school-based training and partly to address some of the weaknesses of the cascade approach. The project focused on school- or cluster-based activities and the lesson study approach. The National Science Centre was designated to be the focal point for the national rollout.

The Kenya and Zambia projects were similar in many ways. Both began with secondary education in a small number of pilot districts and expanded to the entire country and to primary education. Both projects attached special importance to sustainability: partner country governments provided personnel and resources from their budget. Both projects also encountered similar challenges in the expansion to primary education. The core teams had been composed mainly of teachers in secondary schools and sufficient emphasis may not have been assigned to primary school contexts. Although both projects conducted a sort of impact surveys on learning, the results did not show the impact clearly.

The two projects were also different from each other. Kenya’s in-service cascade training system was centrally controlled for content development and implementation quality assurance. Training quality was monitored by national trainers and reported to the national headquarters by training organizations. Zambia adopted a decentralized approach to ensure continuous professional development through school-based training combined with lesson study to improve practical skills. Subject teachers developed better classroom activities as models for others to emulate.

Other projects focused on school management committees

The second type of project, starting with Niger in 2004, focused on engaging school management committees (SMCs) in identifying problems and implementing a plan to tackle them. SMCs focused on improving children’s basic mathematics skills and organized remedial classes using workbooks after school hours.

A prominent example was in Madagascar, where the project evolved in two phases. During the first phase (2016–20), a participatory and decentralized school management improvement model was established in one target region. Schools generally decided to focus on remedial education, which combines the ‘minimum package for quality learning’ (PMAQ) and the ‘Teaching at the Right Level’ (TaRL) approaches. Under the PMAQ, developed in Niger, a school initially assesses basic reading and mathematics, and shares the results with teachers, parents and the community at a general meeting to motivate action. Under TaRL, developed in India, children are grouped based on these results, regardless of their grade. Remedial activities are undertaken after school hours on the school premises mostly by teachers.

An evaluation in 140 schools that were split into a control group and a group that received PMAQ and TaRL interventions found a strong positive impact on basic calculation and reading skills. It has, therefore, been estimated that these skills have improved for 1.2 million primary school students since 2017/18. As the model proved effective, scalable and replicable, the Ministry of Education has been expanding it to 11 regions during the second phase since 2020. Recurrent costs are expected to be borne by national budgets and institutions.

Singling out Japan’s contribution to project activities, including the cost of Japanese experts and their activities, capital equipment purchases and training costs, shows that these three projects have had a low and sustainable per student cost. In the case of Madagascar, “JICA cost” includes the cost not only for improving mathematics learning, but for strengthening SMCs.

Costs of selected JICA-funded primary and secondary education mathematics projects in Africa

Note: During Phase 3 in Zambia, interventions also extended to primary grades.

In recent years, the evaluation of mathematics and early learning projects has focused on demonstrating their short-term impact on learning outcomes. However, drawing conclusions only from such assessments can be misleading because short-term success may not trigger sustainable long term mechanisms for self-improvement. Endogenous curriculum development, teacher competence, knowledge and beliefs, communities of practice, and reflective professional learning have proven important factors in the development of mathematics education and should not be neglected.

The post Japanese international cooperation has supported primary mathematics programmes in Africa for more than two decades appeared first on World Education Blog.

Africa Archives – World Education Blog